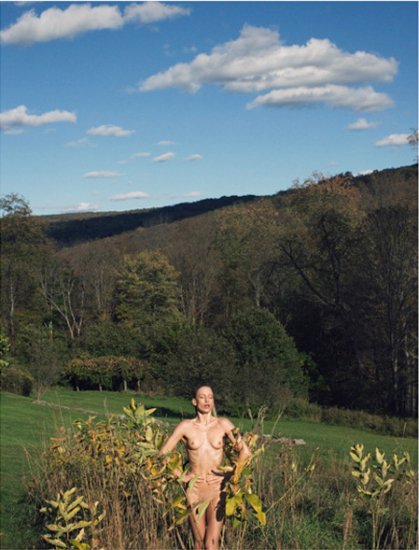

Danko and Ana Steiner are originally from Zagreb, Croatia, but they have spent the majority of their adulthood living as husband and wife in downtown New York. While their artistic collaborations do not directly deal with the political upheaval of their childhood homeland—one, though, that pointedly saw the dissolution of the socialist nation of Yugoslavia into capitalist republics and the rise of ethnic tensions that led to the Bosnian War in the early 1990s—the Steiners’ aesthetic does possess a very galvanized sense of hopeful re-invention. As is the case of anyone who comes from one culture and enters another, there is something of a juggling, a collage, a reassembly of values, ideals, and obsessions to create a fluid surface (where those who have always lived here operate on a no-assembly-required field of vision). Within the five photographs, one collage, and, one sculpture exhibited in this show, there is a sense of freedom and play. But there is also an almost deadly tension between an image of phenomenal beauty and the imminence of its disintegration and loss. Why, for example, does the single shot of the brown velvet sofa seem so unsettling here.

A sofa should mean safety, it should mean home (in fact, it is the sofa in the home of Danko and Ana Steiner). But set alongside these female forms coming in and out of being, there is something potent and dangerous—almost deceptive—about it.

A sofa should mean safety, it should mean home (in fact, it is the sofa in the home of Danko and Ana Steiner). But set alongside these female forms coming in and out of being, there is something potent and dangerous—almost deceptive—about it.

That said, the title of the show, “Baby, We’re Really In Love” perfectly defines the collaboration of this team: one, where more than not their own friends, own clothes, and own apartment form the content of the shoots. There is a quote by Friedrich Nietzsche that goes as follows: “the cure for love is still in most cases that ancient radical medicine: love in return.” Nietzsche, perhaps the first modern cynicist, means here that the return of someone’s love destroys your love for them. But what if we take this quote literally on its faulty English translation: The cure for love is love: the fixing of love doesn’t mean love’s termination but the finding of its own kind. Love is of course the magical interlude in times of crisis—or love is a crisis that trumps all others. In the work of the Steiners there is a great sense of love keeping their subjects going—particularly a love of New York City, in all of its seedy corners, loud music, cultish figures, dark alleys, bad trips—basically the whole back history of the East Village neighborhood where in which the Steiners live. If these were simply “fashion photographs,” the pallid, almost death-mask makeup on one model would be an offense to the clean white cap promoting NYC in the most generic touristic terms. Similarly, we see Chloe Sevigny, a contemporary New York icon, whose presence—if only we could make out her face—would guarantee magazine sales. But the Steiners’ have consolidated Sevigny into a very different and

far more subversive New York icon, that of 70s porn star and downtown fixture Peter Berlin. The Steiners’ have, in a sense, overlaid their own love of a certain idea of radical New York on top of another more current idea of radical New York.

Ultimately, there is a feeling of death but also celebration, a sense of things falling away but also a love for making what we can. Quite big issues, but ones we battle every day—at least we do in New York.

by Christopher Bollen

Ultimately, there is a feeling of death but also celebration, a sense of things falling away but also a love for making what we can. Quite big issues, but ones we battle every day—at least we do in New York.

by Christopher Bollen