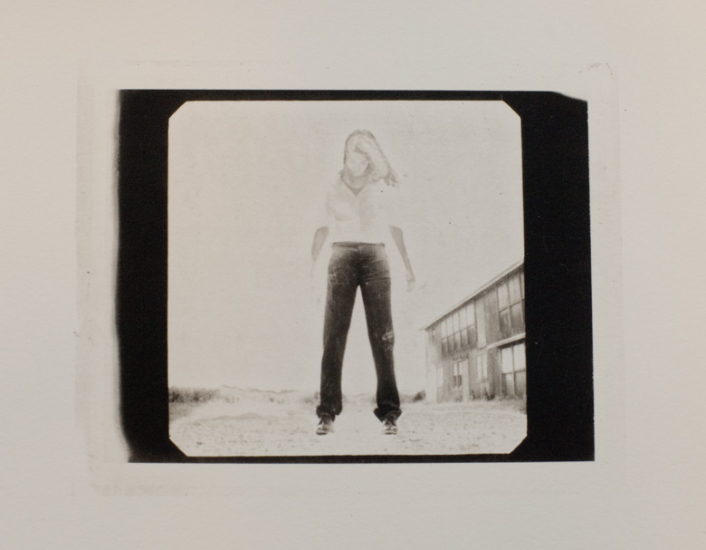

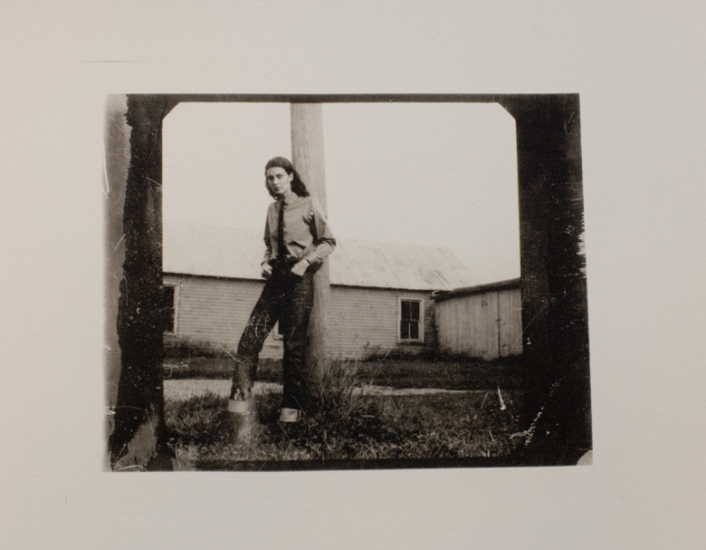

High Noon: The gunslinger counts her paces before she turns to draw the gun for the duel. Her arms are held slightly away from her body, at the ready, the white sleeves flutter, evoking the sound of dry winds and the dissonant chord of a trip hop remix of an Ennio Morricone score. One crucial detail is missing: the gun.

Elfie Semotan’s series MALE GESTURES created for Allure in 1998 proves again the power of omissions. Often in her photographs it is the absence of the obvious that brings about the essence. She gruffly reverts the predictable caricature of the Western genre: the cowboy has no cow, the trigger-happy gunslinger is stripped of his revolver, the big heroic gesture goes without the gesture.

The story of a fashion shoot is rarely told by the clothes but more so by the concept of the author, the choice of location and the model. Semotan uses the possibility of the photographic mise-en-scène to create an infraseductive metanarrative for fashion, whose story ventures beyond the photographic frame by allowing the viewers their own private scriptwriting orgies in their minds. Location, props and lighting are carefully chosen and worked into a tight concept, the drama as gripping and as chilled as a polar bear’s snout.

Semotan points out that for her work in the fashion industry she needed to salvage the clothes from the dismal ghetto seasonal garments are confined to. Though clothes are a substantial part of her story, they are never on obvious display and therefore elegantly escape the banal. Then again, what they escape from may be the banalization of the elegance, I’m never quite sure.

So Semotan was asked to show a woman in men’s clothes. An approach that has been widely canonized in Peter Lindbergh’s iconographic imagery of supermodels with dark-rimmed eyes, short cropped wigs, sometimes smeared with remnants of fake oil

Elfie Semotan’s series MALE GESTURES created for Allure in 1998 proves again the power of omissions. Often in her photographs it is the absence of the obvious that brings about the essence. She gruffly reverts the predictable caricature of the Western genre: the cowboy has no cow, the trigger-happy gunslinger is stripped of his revolver, the big heroic gesture goes without the gesture.

The story of a fashion shoot is rarely told by the clothes but more so by the concept of the author, the choice of location and the model. Semotan uses the possibility of the photographic mise-en-scène to create an infraseductive metanarrative for fashion, whose story ventures beyond the photographic frame by allowing the viewers their own private scriptwriting orgies in their minds. Location, props and lighting are carefully chosen and worked into a tight concept, the drama as gripping and as chilled as a polar bear’s snout.

Semotan points out that for her work in the fashion industry she needed to salvage the clothes from the dismal ghetto seasonal garments are confined to. Though clothes are a substantial part of her story, they are never on obvious display and therefore elegantly escape the banal. Then again, what they escape from may be the banalization of the elegance, I’m never quite sure.

So Semotan was asked to show a woman in men’s clothes. An approach that has been widely canonized in Peter Lindbergh’s iconographic imagery of supermodels with dark-rimmed eyes, short cropped wigs, sometimes smeared with remnants of fake oil

and dirt. Phantasmatic tableaux of nostalgie de la boue that exists only on and for the pages of glossy magazines. Semotan wanted to revert this highly aestheticised approach of women coyly impersonating men who were in some ways coyly empersonating women.

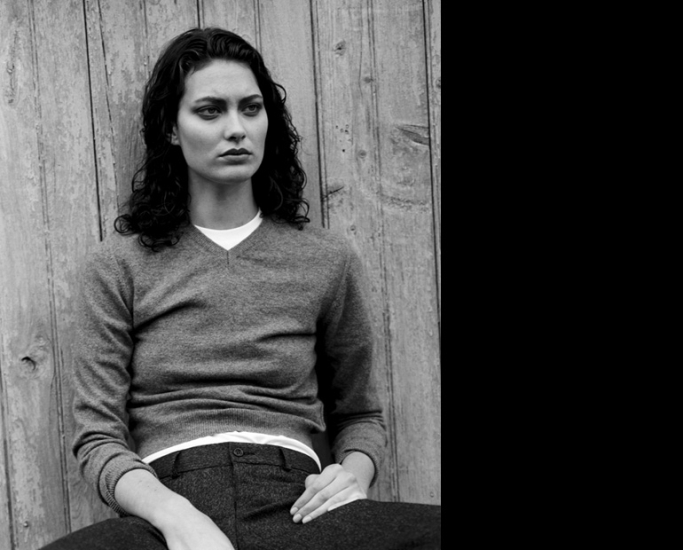

Semotan stripped model Shalom Harlow of all the attributes she is best known for: grace, charm, elegance and femininity. She broke the fashion photography dictum of pleasing or appealing and portray her in the way “men like to see themselves, the way they would like to be portrayed,“ she says.

The images and the gestures may be inspired by Western heroes, and the latter day glitterati admirers of western heroes, but again the photographer opts for the omission of that grand pose: determined gaze, squared shoulders, compulsive cigarette smoking. These pictures reveal what in an ideal world would be the core of masculinity: a person who is self-assured, relaxed, drawing power from the simple fact that he is a man.

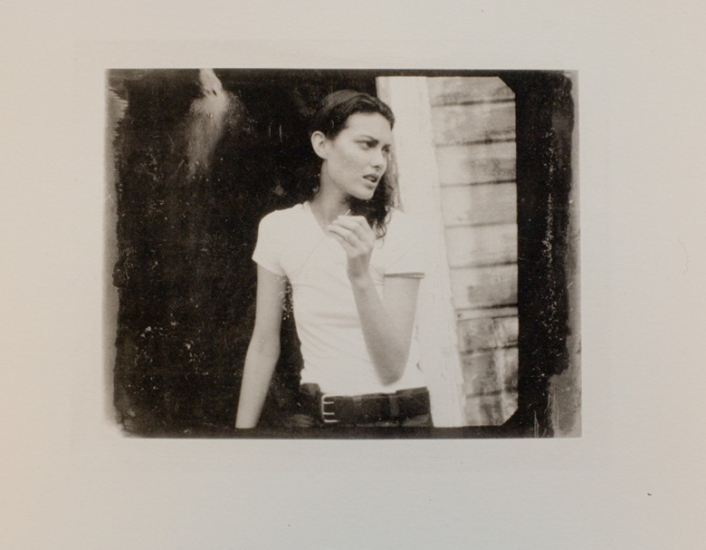

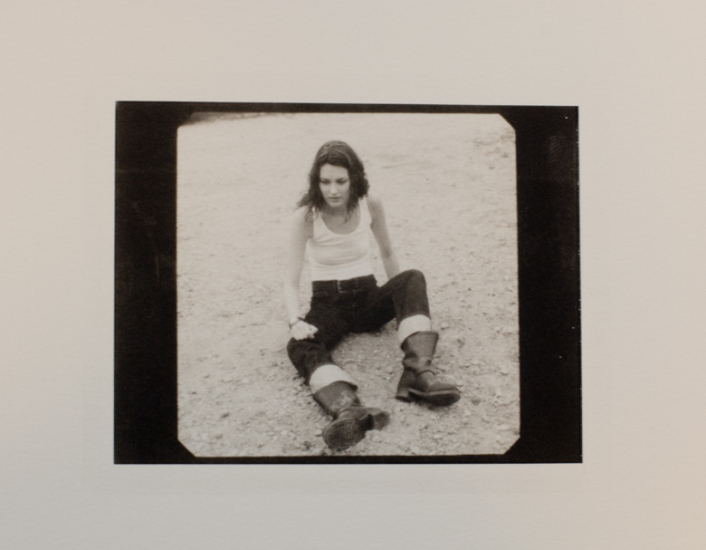

For this exhibition Semotan dug into her archive and found Polaroids, quick light studies with Harlow on location. The rough black and white material had disintegrated and feels underwhelming and as whoozy as the human memoria. One of these show a ghost-like Harlow, the gunslinger unslung. Semotan re-printed the Polaroids using platinum processing technique, which basically renders photos eternal. Lens wizard Edward Steichen used it for his early 20th century VOGUE fashion shoots of Greta Garbo super-glam.

If it wasn’t for Semotan’s strong visual narrative the fashion worn in the MALE GESTURES series would have long been considered historical in the worst sense of the world. What we see here is timeless. Only better.

By Eva Munz

Semotan stripped model Shalom Harlow of all the attributes she is best known for: grace, charm, elegance and femininity. She broke the fashion photography dictum of pleasing or appealing and portray her in the way “men like to see themselves, the way they would like to be portrayed,“ she says.

The images and the gestures may be inspired by Western heroes, and the latter day glitterati admirers of western heroes, but again the photographer opts for the omission of that grand pose: determined gaze, squared shoulders, compulsive cigarette smoking. These pictures reveal what in an ideal world would be the core of masculinity: a person who is self-assured, relaxed, drawing power from the simple fact that he is a man.

For this exhibition Semotan dug into her archive and found Polaroids, quick light studies with Harlow on location. The rough black and white material had disintegrated and feels underwhelming and as whoozy as the human memoria. One of these show a ghost-like Harlow, the gunslinger unslung. Semotan re-printed the Polaroids using platinum processing technique, which basically renders photos eternal. Lens wizard Edward Steichen used it for his early 20th century VOGUE fashion shoots of Greta Garbo super-glam.

If it wasn’t for Semotan’s strong visual narrative the fashion worn in the MALE GESTURES series would have long been considered historical in the worst sense of the world. What we see here is timeless. Only better.

By Eva Munz