Paul Rousteau came to photography by chance, as it were. It must have been sometime in

winter, around Christmas time, when the then-sixteen-year-old young man was wandering around the foggy landscape of Alsace with a friend. On a whim they had brought along his father’s camera. They weren’t up to anything in particular until Rousteau started snapping

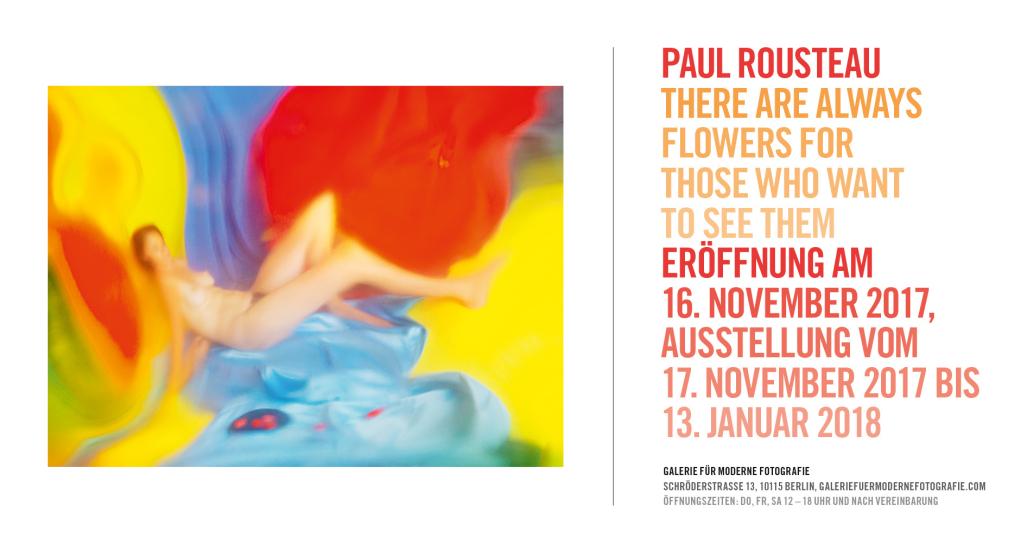

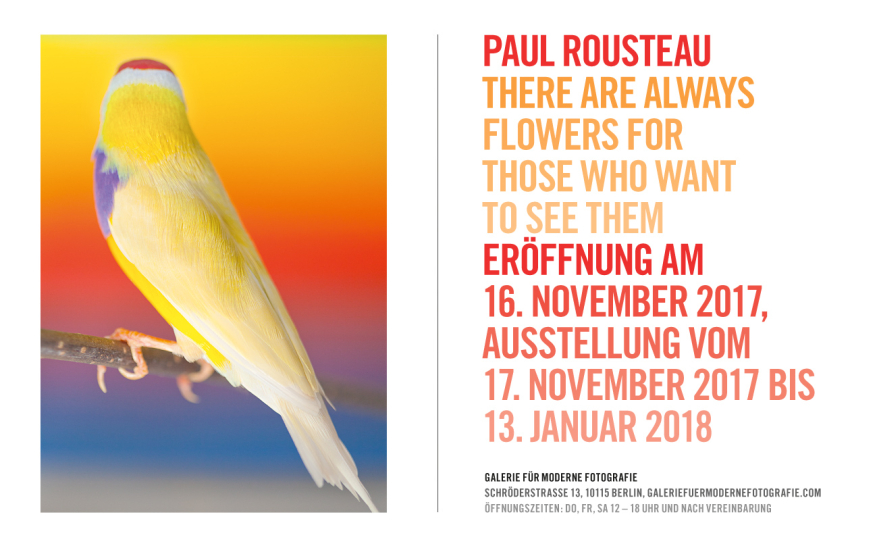

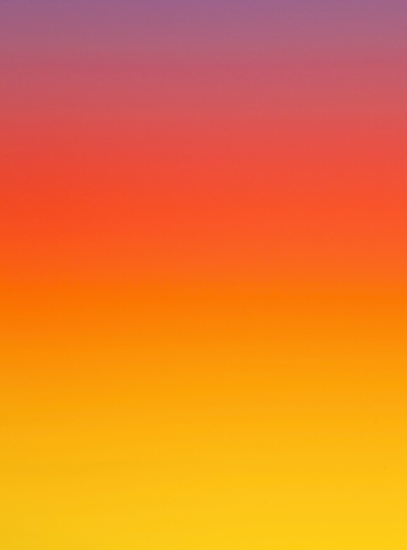

away just for fun: at nature in the dim light. At a crib somewhere on the side of the road. He discovered that he liked this medium, so he became a photographer. Sixteen years later, he calls himself a “naive” type. Perhaps because the themes he happened upon then have not wavered—his love of nature, flowers, birds, of a particular fundamentality and simplicity. But perhaps also simply because the way he looks at things is different. After moving to Paris almost seven years ago after studying art in Belgium and photography in Switzerland, Rousteau came to the realization that his luminous images made him stand out among his peers like a far too colorful outsider. Like a rare bird: while everyone else was snapping images of gritty suburbs, ruins, pain, and decay, he used his camera to probe the inside of a flower blossom to explore its hidden truth. Instead of focusing on the city, social problems, injustices, or similar contemporary public realities, the young photographer turned his eye inward. Toward the private, a particular domesticity: In his images—many of them part of a book designed for his son—one sees the rounded belly of his pregnant girlfriend, bananas, apples, lemons, still lifes extracted from his everyday life as a young father, flowers and butterflies, the naked little bodies of his children, a particularly beautiful sunset. They are the images of a paradise—that of the children, the innocent, perhaps the naive. Each of them bathed in warm Californian colors therefore, often a bit blurred, like watercolors, somewhat fleeting, like a dream right after waking. Abstraction is never far off, his photographs are pure impressions; some recall the sfumato of Sarah Moon, many the interplay of light and color of dancer Loie Fuller. Rousteau calls them mental landscapes, direct translations of his clearly very colorful perceptions. In all their luminous cheerfulness, however, they are above all also expressions of a particular melancholy transformed into images. Ones that are no longer so naive, that refuse to let go of this childlike capacity to find delight in the grandiosity, the overwhelming beauty of a meadow, a sky, a banal flower, a particular color nuance or unexpected atmospheric light. The name of the exhibition There are always flowers for those who want to see them, a quote by Henri Matisse, a painter the photographer greatly admires along with Monet or Bonnard, attests to this melancholy—to the desire to never loose the capacity to see flowers. At thirty-two, Paul Rousteau has nearly achieved his goal of “making the invisible visible”: with his camera he seems to strip away all the gray filters that life, experience, and time have deposited layer-like over our eyes. In his images one sees the fundamental illuminated. And it is extremely beautiful. Text: Annabelle Hirsch

For further information and picture material please contact: Kirsten Landwehr, mail@galeriefuermodernefotografie.com

winter, around Christmas time, when the then-sixteen-year-old young man was wandering around the foggy landscape of Alsace with a friend. On a whim they had brought along his father’s camera. They weren’t up to anything in particular until Rousteau started snapping

away just for fun: at nature in the dim light. At a crib somewhere on the side of the road. He discovered that he liked this medium, so he became a photographer. Sixteen years later, he calls himself a “naive” type. Perhaps because the themes he happened upon then have not wavered—his love of nature, flowers, birds, of a particular fundamentality and simplicity. But perhaps also simply because the way he looks at things is different. After moving to Paris almost seven years ago after studying art in Belgium and photography in Switzerland, Rousteau came to the realization that his luminous images made him stand out among his peers like a far too colorful outsider. Like a rare bird: while everyone else was snapping images of gritty suburbs, ruins, pain, and decay, he used his camera to probe the inside of a flower blossom to explore its hidden truth. Instead of focusing on the city, social problems, injustices, or similar contemporary public realities, the young photographer turned his eye inward. Toward the private, a particular domesticity: In his images—many of them part of a book designed for his son—one sees the rounded belly of his pregnant girlfriend, bananas, apples, lemons, still lifes extracted from his everyday life as a young father, flowers and butterflies, the naked little bodies of his children, a particularly beautiful sunset. They are the images of a paradise—that of the children, the innocent, perhaps the naive. Each of them bathed in warm Californian colors therefore, often a bit blurred, like watercolors, somewhat fleeting, like a dream right after waking. Abstraction is never far off, his photographs are pure impressions; some recall the sfumato of Sarah Moon, many the interplay of light and color of dancer Loie Fuller. Rousteau calls them mental landscapes, direct translations of his clearly very colorful perceptions. In all their luminous cheerfulness, however, they are above all also expressions of a particular melancholy transformed into images. Ones that are no longer so naive, that refuse to let go of this childlike capacity to find delight in the grandiosity, the overwhelming beauty of a meadow, a sky, a banal flower, a particular color nuance or unexpected atmospheric light. The name of the exhibition There are always flowers for those who want to see them, a quote by Henri Matisse, a painter the photographer greatly admires along with Monet or Bonnard, attests to this melancholy—to the desire to never loose the capacity to see flowers. At thirty-two, Paul Rousteau has nearly achieved his goal of “making the invisible visible”: with his camera he seems to strip away all the gray filters that life, experience, and time have deposited layer-like over our eyes. In his images one sees the fundamental illuminated. And it is extremely beautiful. Text: Annabelle Hirsch

For further information and picture material please contact: Kirsten Landwehr, mail@galeriefuermodernefotografie.com

Paul Rousteau